Àdùnní Olórìsà: Priestess and Art Champion

There are several interesting things about Àdùnní Olórìsà, Priestess of the goddess Òsun and guardian of the Sacred Groves on the banks of the Òsun River in Òsogbo, but perhaps the most intriguing is the fact that she was a white woman. Born Susanne Wenger on the 4th of July 1915 in Graz, southern Austria during WWI, she grew up wandering the woods and mountains of Graz and developed a love for nature at an early age. She studied at the College for Arts and Crafts in Graz and the Academy of Art in Vienna.

Her early works featured pencil, ink and crayon drawings, pottery, fresco and ceramic works. During WWII, Susanne offered help to Jews and other people facing political persecution in the then Nazi-occupied Vienna. The Nazi regime declared her Art degenerate, Entartete Kunst, and forbade her to paint. It was at this time that she turned to books on foreign religions for relief. She became interested in how communication between the divine and humanity was achieved by different religions. Living through WWII brought on disturbing dreams, and the pictures she sketched of her dreams during this time have been proclaimed by Art experts as the first Austrian surreal works of art. Her sketches took the form of hybrid creatures and abstract images in interpreting the reign of terror and the war itself in a surreal way.

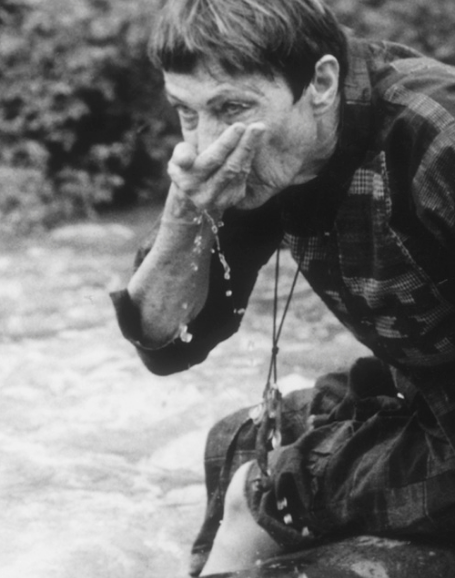

After the war, she continued to experiment with Art that drew inspiration from spiritualism, shamanism, psychoanalysis and the metaphysical. She would often retreat into the mountains for long periods, painting, sketching, and reflecting in nature. This, she said, gave her inspiration and energy. A vast majority of her work featured surreal pictures and images with hard-to-decipher iconography. She believed art to be an archaic language shared by all mankind irrespective of their culture or religion. Some of her early tachisme-style drawings show her interest in pantheism even before she encountered the Yorùbá religion, and depict quasi-visions of the shrines she would one day revive and rehabilitate. Two of her works that were published in a cultural journal between 1943 and 1944 were negatively received and discredited, and she was declared mentally abnormal by the critics of the time.

In 1946, she co-founded the Art Club, an international association promoting the right to artistic freedom, and she was a part of the avant-garde scene of the early post-war period. Between 1946 and 1948, she worked as a cover illustrator for the children’s magazine Unsere Zeitung, creating illustrations and cover designs that stood out. In 1948, she was invited by art dealer Johan Egger to the Abstrakt–Konkret artist group in Zurich. She moved to Paris in 1949 where she met Ulli Beier, a German-British linguist. When Beier was offered a position as a phonetician at the University of Ibadan, a position which was restricted to only married applicants, the couple decided to get married in London so he could take the position. This decision, made seemingly on a whim, was going to change the course of Susanne’s entire life.

The couple moved to Nigeria, driving across the Atlas Mountains and the Sahara desert of North Africa. When they arrived at the University campus, they were disappointed by the atmosphere, which they described as “artificial”. This was a result of the culture on the campus being predominantly post-colonial European, which they found was too westernized for them. They didn’t get the opportunities they had hoped for to interact and connect with the local people and their traditions. This led Beier to transfer to the Extramural Studies department and to begin teaching English classes to the locals in the surrounding cities.

Their travels brought them across a mental hospital in Abéòkuta where they organized painting classes for the patients. They held an exhibition titled Psychotic Art at the University of Ibadan, showcasing the art made by the patients. Both Susanne and Ulli were interested in the concept of Art Brut, or Outsider Art, art made by self-taught artists whose art had been developed outside of prevailing conventions or aesthetics, and without formal education and training. Beier went on to found an experimental art school for Outsider Artists in Òsogbo, helping to nurture a generation of Nigerian artists who emerged from the school.

Ulli Beier wrote extensively on a varied number of Yorùbá topics including art, oral and written literature, and drama, and several of his written work can be found at the Center for Black Culture and International Understanding in Òṣogbo and at the Ìwàlewà Haus at the Bayreuth University, Germany. He translated several works of Yorùbá poetry, myths, and proverbs into English, as well as writing original prose under the pen name Òbótúndé Ìjímèrè. He was influential in the introduction of several notable Nigerian literary icons to the international world including Wọlé Ṣóyínká, Chinua Achebe and Dúró Ládípò. With Wọlé Ṣóyínká and Chinua Achebe, he founded the Mbárí Club in Ìbàdàn, and the Mbárí Mbáyò club in Òṣogbo.

Susanne’s journey of immersion into Yorùbá culture and spirituality began when she became very ill with tuberculosis. She went through a long recovery process during which she read anthropological books about the Yorùbá people and culture. Susanne also painted several fantastical and surreal pictures on wooden panels while she lay in bed. She started to feel a strong attraction to the culture, especially the sacred worship of the òrìsàs, the gods. Later, she would state that she believed her illness had been a sacrifice of sorts for the knowledge that she would receive from the gods.

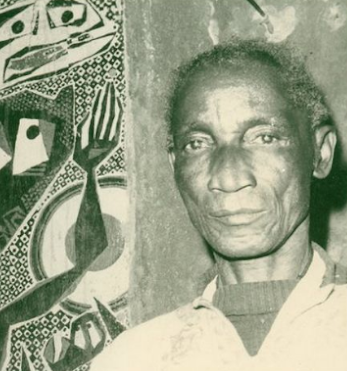

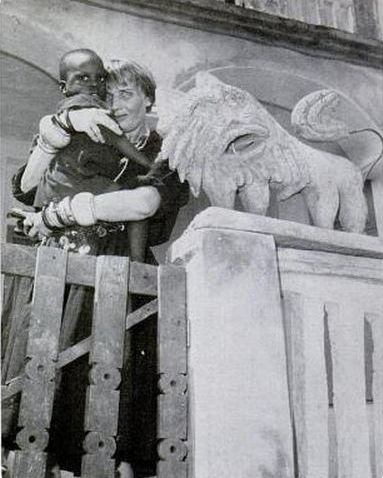

A chance encounter in the town of Ede marked the beginning of her friendship with Ajágemo. She was drawn to the sounds of drums one day as she walked through the neighbourhood, and the sounds led her to a shrine. Ajágemo, who was a priest of the god Òbàtálá, welcomed her into the courtyard. The two struck off an instant connection and Ajágemo introduced her to the Yorùbá language, religion and worldview. He became more than just a friend to her; he became her mentor and spiritual father. He seemed to have recognized something in her that he then went on to nurture. Ajágemo, himself an archaic man, had divined in advance that she would be instrumental in the worship and preservation of the òrìsàs. She, in turn, was the model student, quickly getting a grasp of the language and symbolism of the òrìsà religion. She underwent an initiation process which took several years, after which the position and title of Olórìsà, which depicts an adherent of a deity, were bestowed upon her. From then on, her ritual name became Àdùnní Olórìsà. She was also initiated into the priesthood of Sòpòná, as well as the Ògboni fraternity.

During this time, she embraced the African arts of Àdìre and Batik. She created vivid and colorful murals and wall hangings depicting the stories of the gods, using symbolism and drawing from mythology. She painted interpretations of Yorùbá mythology using pieces of cloth stitched together to form huge monochrome canvasses. It wasn’t so much that she was “influenced” by African art, but that African life impacted her imagination and creativity. The restrictions and constraints she had experienced in the European art scene gave way to freedom and acceptance within her adopted community.

Even though her work and style were different from the existing indigenous art of the time, they were accepted and even celebrated as offerings to and honoring the gods. At the core of Susanne’s art was the intricate marriage of art and religion and her main goal was to protect the sacredness of nature. She tried to embody the myths and unique characteristics of the gods in her sculptures and murals. She believed that the life of an artist is beyond time and is singularly devoted to the work of bringing rebirth in the circle of being.

One thing Susanne fast discovered about her newfound religion was that it was dying out quickly and that a lot of the sacred shrines and artifacts were suffering from neglect, vandalism, and total eradication in some cases. A big reason for this was colonization and missionary activity. Western influence in post-colonial Nigeria had led to the pagan religions being considered primitive and backward and had been branded black magic, jùjú. The language of the culture was also under threat of extinction, with the Anglicisation and adaptation of its characters to western models. This all resulted in the gradual decay and disintegration of the culture and the neglect and imminent death of the worship of the òrìsàs. It also meant that the local artists, many of whom were descended from generations of guilds of artists who had been specially commissioned to serve the òrìsàs, were losing their place in society as well as their means of sustenance.

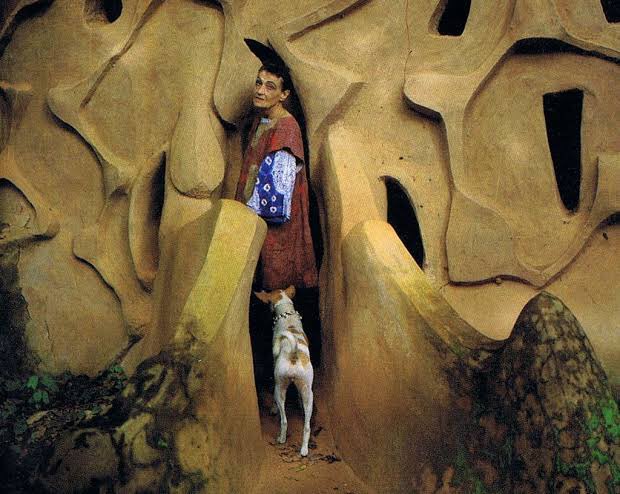

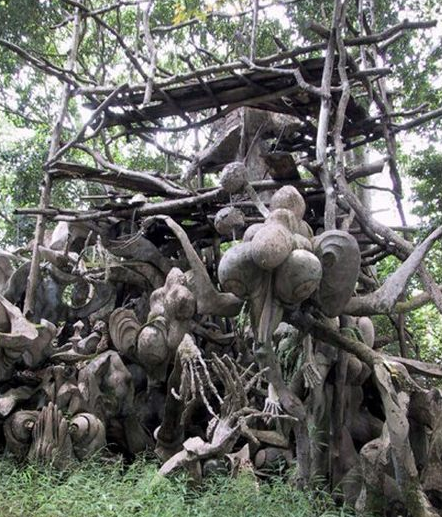

Susanne was invited by the head Priestess of the river goddess Òsun, who had heard of her work in the shrines of Òbàtálá and her spiritual devotion to the gods, to help with the sacred groves in Òsogbo, a 75-hectare old-growth forest which is known as the sacred home of the spirits of the river and trees. With assistance from a young craftsman, Adébísi Àkànjí, who taught her the technique of cement sculpting, she started with the restoration of the shrine of goddess Òsun, Osùbo Òsogbo, which was being destroyed by termites. She also had help from other local artists including Foyèké Àjoké and Sòngó Túndùn, who were both women and created shrine paintings, Kàsálí Àkàngbé-Ògún, Rábíù Abesu, Búráímò Gbàdàmósí, Sàká Àrèmú, Ajíbíìké Ògúnyemí, Òjéwolé Àmòó, Ásírù Oládépò, and Sàngódáre Àjàlá, one of her adopted sons.

Apart from the works of restoration, Susanne encouraged these artists to produce their own relief ornaments; she never undertook to teach or train them but encouraged them to allow the sanctity of the forest, the river and the deities to inspire them. Susan was also tasked with building a portal into the grove, a task which she felt honoured to take on. In addition, she worked on the shrine of Sòpòná, the Ìdí Baba shrine; the Iléèdí Onítòótó, the shrine of the earth god and the gathering place of the Ògboni; the shrine of the Earth Mother, Ìyá Moòpó; the restoration of the Chameleon Gate, leading to Ebu Ìyá Mọòpó; the marketplace; and the Arch of the Flying Tortoise, the original sculpted arch at the entrance to the Sacred Grove. After the completion of these works, she committed herself to the service of the goddess Òsun. Between the 1960s and the early 2000s, she created a sculpture complex in and around the sacred grove.

The battle to preserve the sacred groves was a tug of war, with opposition coming from several fronts. She faced criticism from the Christian and Muslim missionaries who opposed the revival of the pagan religions. There was also a lot of pushback from locals: farmers who wanted to cut down the trees in the grove to create farmland, poachers who wanted to hunt the wildlife, and even town encroachment. The restoration of the Grove and the revival of the worship of the òrìsàs resulted in the return to honouring the ancient pact with the goddess Òsun to treat the grove as sacred and to desist from fishing, farming or hunting within the Grove. This wasn’t well taken by those who sought to commercialize the Grove. Susanne was once reported to have lain in the path of a bulldozer that had been brought in to clear a portion of the Grove for the construction of a house.

Funds for these restorative works came partly from the Antiquities and Monuments Office in Lagos and the Òsogbo District Council, but mostly from the sale of Susanne’s artwork. From the mid-1980s, Susanne had many exhibitions around the world. In 1985, she had an exhibition in Vienna, the first time she had returned there in 35 years. In 1992, she exhibited in Prague, and Bayreuth in 1993. In 1995, the Kunsthalle Krems held an exhibition in the Minoritenkirche, showcasing works from the New Sacred Art Movement. She took part in Okwui Envezor’s exhibition on post-colonial Africa in Munich, Berlin, Chicago, and New York in 2001. In 2004, an exhibition titled “Along the Banks of a River in Africa” was held in her hometown, Graz. A huge collection of her artwork is conserved in a gallery in Krems, Austria.

In 1965, the Grove was made a National Monument by the Nigerian Government and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. She was decorated with the Silver Order of Art and Science by the Federal Republic of Austria in 2001, the highest order of the Government of Lower Austria. She was admitted by the Nigerian Government into the Order of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (OFR) in 2005. She was also bestowed with a chieftaincy title by the Ataojà of Òsogbo. Her work in the Grove is the subject of The Oshun Diaries, a memoir by Diane Esguerra, published in 2019.

In 1958, Susanne and Ulli Beier divorced as a result of their differing views and the focus of their different works. Susanne disagreed with and distanced herself from Ulli’s Eurocentric worldviews. He was more interested in the development of contemporary art in Nigeria while she focused on the archaic art and culture of the Yorùbá people. Susan later married local drummer Làsísì Àyánsolá Onílù but they divorced as well.

Her home in the now famous stone house in Ìbòkun Road, Òsogbo, which she shared first with Beier and then Àyánsolá, showcases her art, many of the furniture depicting different aspects of the Yorùbá culture and religion. She developed a technique that combined textile painting, batik and indigo dyes to create quite impressive fabric art.

Susan adopted more than 15 children during her lifetime. Among them are well-known Nigerian painter, Yinká Davis-Òkúndàyè, Chief-priestess Adédoyin Fáníyì, and Chief-priest Sàngódáre Àjàlá, who worked alongside her in the restorative works of the Grove. Between 1952 and 1970, Susanne designed covers for and illustrated books by Yorùbá authors. She also wrote and illustrated children’s books, both in English and Yorùbá, as well as contributing content to the Black Orpheus Magazine which had been founded by Ulli Beier. In 1953, she published the first-ever alphabet book for primary schools in Yorùbá. Her book, “A Life with the Gods”, was published in 1982, with photographs taken by renowned photographer Gerd Chesi.

In the early 1960s, she developed, in collaboration with a group of traditional artists and artisans who she mentored, the Archaic-Modern Art school called the New Sacred Art Movement which is unique to Nigeria and is recognized globally as an important form of artistic expression. Susan referred to the monumental shrines, decorative walls and sculptures located throughout the Sacred Groves as “New Sacred Art”. She created a cooperative society to help support the artists of the New Sacred Art Movement.

Susanne Wenger, Àdùnní Olórìsà, died on January 12th, 2009, at the age of 93. Burial rites were performed in the Sacred Grove by worshippers of Orò and Òsun. It was Susanne’s wish to be buried without any fanfare and for her final resting place to be within the Grove. Susanne Wenger passed on the torch to several individuals and organizations committed to continuing her work and upholding her legacy: The Àdùnní Olórìsà Trust; The Àdùnní Òsun Foundation; The Susanne Wenger Foundation (Krems, Austria); and The New Sacred Art Movement.

Sources:

Aragbabalu, O. (2018). The Art of Susanne Wenger. https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files2/asapr60.18.pdf

Ayangalu. (2019). History Of Susan Wenger An Austrian Olorisa Priestess Aka Adunni Olorisha. https://ooduarere.com/news-from-nigeria/breaking-news/susan-wenger-adunni-olorisha/3/

Borchhardt-Birbaumer, B., Schantl, A. (n.d.). Susanne Wenger – “Art is Ritual”. Susanne Wenger Foundation. https://susannewengerfoundation.at/en/susanne-wenger-art-ritual

Guicheney, P. (2001). Susanne Wenger, a portrait. http://pierre-guicheney.eklablog.com/susanne-wenger-un-portrait-p417306

Indigo Arts Gallery. (2009). Susanne Wenger (Adunni Olorisha). https://indigoarts.com/artists/susanne-wenger-adunni-olorisha

Joffroy, T. (n.d.). Osun–Osogbo Sacred Grove. UNESCO World Heritage Collection. https://whc.unesco.org/fr/list/1118/gallery/

Johnson, S., Falola, T., Law, R., Adebanji, S., Hinderer, A., Biobaku, S., Verger, P.F. & Peel, J.D.Y. (2020). Susanne Wenger alias Adùnní Olórìṣà (1915 – 2009). Nigeria Nostalgia Project. https://twitter.com/yorubahistory/status/1243868146009808897?lang=en

Kufo TV. (2019). Chief Susanne Wenger MFR. https://www.facebook.com/kufotv/photos/a.258600658401443/428121501449357/?type=3

Lambiek Comiclopedia. (2022). Susanne Wenger. https://www.lambiek.net/artists/w/wenger_susanne.htm

Naumann, L. (2020). Susanne Wenger. Aware: Archives of Women Artists Research & Exhibitions. https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/susanne-wenger/

Olademo, O. (2019). Susanne Wenger, a decade after the glow. The Guardian. https://guardian.ng/art/susanne-wenger-a-decade-after-the-glow/

Richards, K. (2009). Suzanne Wenger. The Guardian Obituary. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/mar/26/obituary-suzanne-wenger

Túbọ̀sún, K. (2020). Ulli Beier at the British Library. British Library: Asian and African Studies Blog. https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2020/03/ulli-beier-at-the-british-library.html

Walker, A. (2008). The white priestess of ‘black magic’. BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7595841.stm