Ashes for Beauty: The Journey of a Hundred and Twenty-Three Years

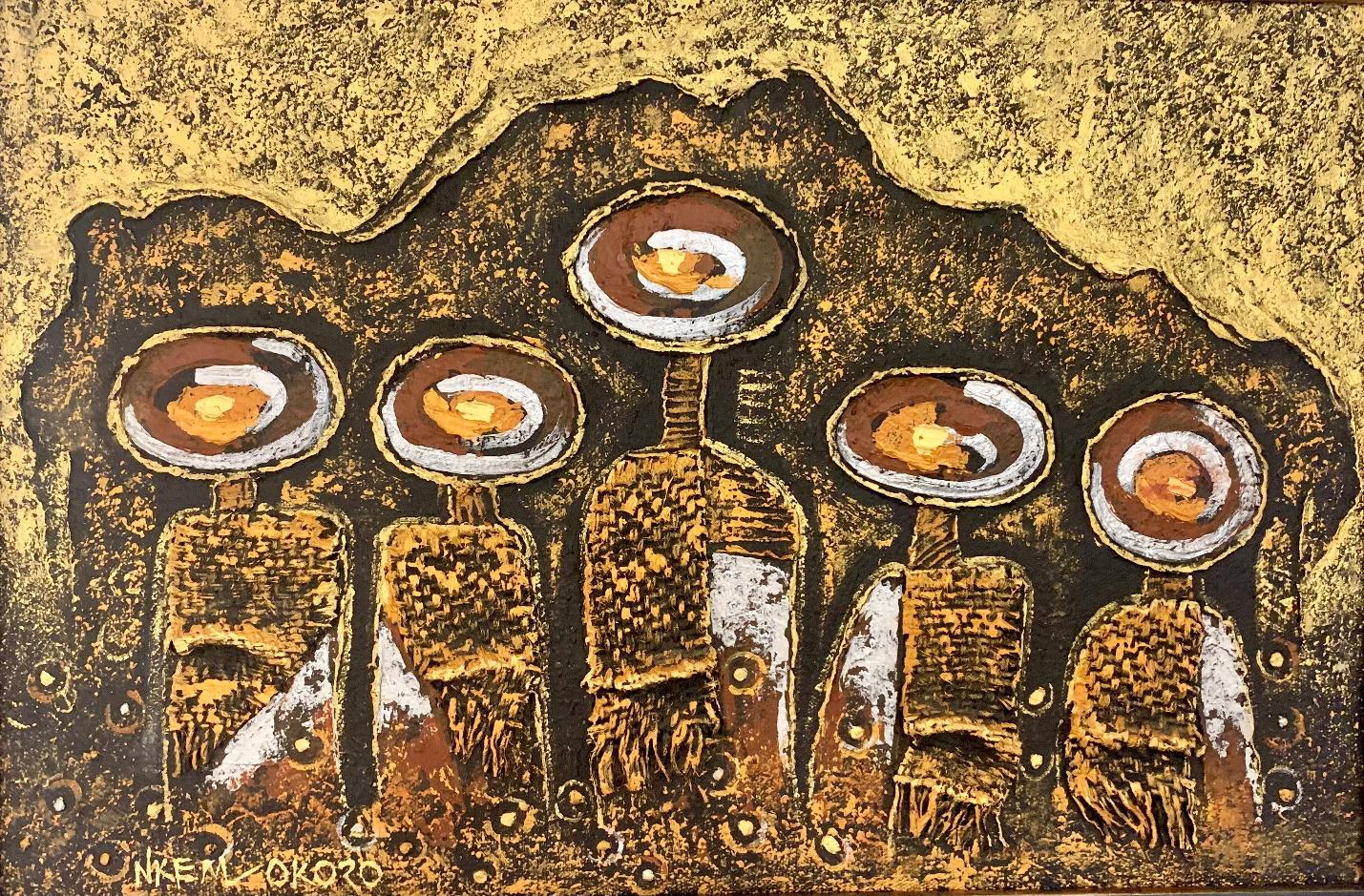

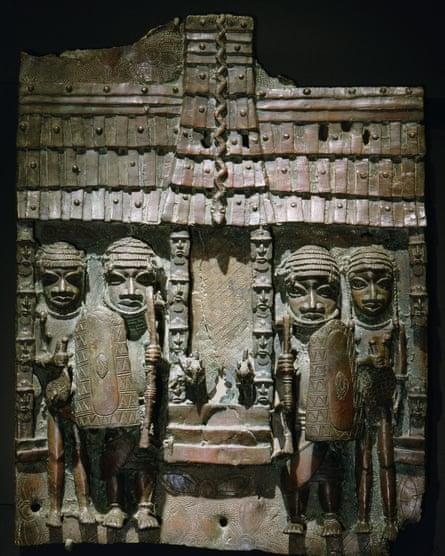

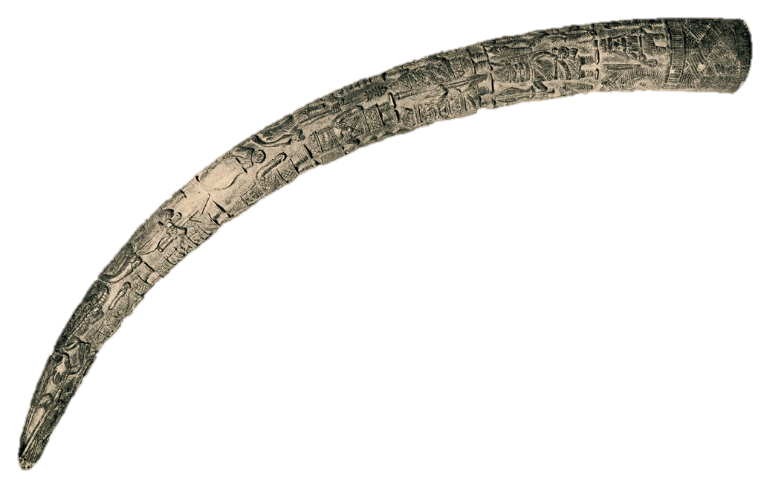

Nkem Okoro’s “Elders” depicts five Benin bronze heads from the ancient Benin Empire (also known as the Benin Kingdom or the Edo Kingdom) which occupied present-day Edo State in southern Nigeria from around the twelfth century until the nineteenth century. The bronze heads (which are not actually fashioned from bronze, but were erroneously labelled as such by the British who first took them to the western world) are a part of works of art produced by special guilds of Benin artists attached to the royal courts, collectively known as the Benin Bronzes. These works include carved elephant tusks, ivory statues, brass plaques, and wooden sculptures. They were primarily commissioned for the ancestral shrines of past Kings (Oba) in the courts of the reigning Obas who were not only revered as traditional rulers but were also believed to be divine and operated in political, judicial, economic, and spiritual capacities. A great number of these works were of the Obas and Queen Mothers (Iyoba), as well as the Oba’s chiefs, warriors and courtiers.

The royal arts of the Benin Kingdom were used to chronicle the history of the Kingdom, the reigns of past Obas and their achievements and conquests, as well as to honour and celebrate them. They detailed the activities of the King’s court, religious rites and rituals, and traditional festivals and celebrations. They also signified the Obas’ worldly and supernatural influence and the extent of their wealth. The materials used for these royal arts, especially brass, ivory and coral, were believed to be sacred and imbued with supernatural power, making them indubitable symbols of wealth and influence among the Benin people. An immense amount of time and skill went into the production of these pieces, again affirming the reverence and worth placed on the Obas and the people’s belief in their otherworldly influence. The metal pieces, like the Oba bronze heads, were made using the lost-wax casting process (also called cire-perdue) and are considered among the best sculptures made using this technique. When these works first arrived in Europe, scholars were astounded that such craftsmanship could be African, and they assumed that the pieces had been influenced by European art.

For the Benin people, these artifacts are not simply works of art, but hold spiritual and cultural value, and are of great importance to them. With no system of writing, the history of the ancient Benin Empire was passed down from generation to generation through stories told orally and through art. Their intricate art was their history, the essence of their culture, their heritage, the beautiful language with which they told their stories. It was the representation of their social institutions and their legacy. The pillaging of this art was akin to ripping out the heart of this civilization and sucking out its soul.

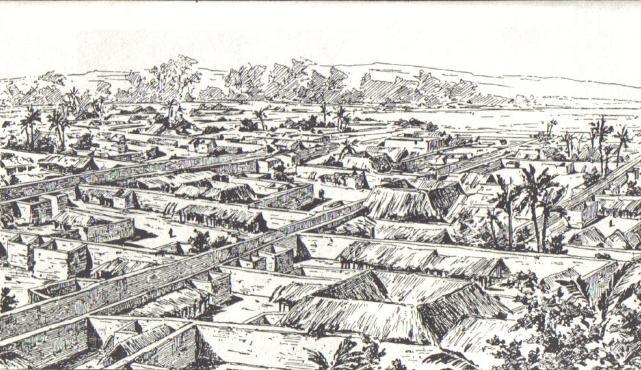

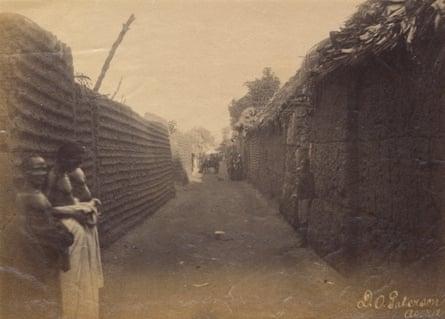

The Benin Empire was one of the oldest and most developed kingdoms of West Africa. It existed from about the 11th century AD until 1897 when it was annexed by the British Empire. The 1974 edition of the Guinness Book of Records described the walls of Benin City, the capital of the Benin Empire, as the world’s largest earthworks carried out before the mechanical era. According to Science writer Fred Pearce, the walls extended over 16, 000 Km in a mosaic of over 500 interconnected settlement boundaries, covered about 6, 500 Sq Km, and were at one point four times longer than the Great Wall of China.

The city was designed using the rules of symmetry, proportionality and repetition of fractals at a time when that mathematical phenomenon was not widely known or studied. Within the city stood the Oba’s court, the jewel at the heart of the necklace. It was within the palace that the majority of the Bronzes were displayed. The Oba’s palace was a conglomeration of buildings and courtyards with gallery-like passages. Brass plaques with relief images decorated pillars, arches and posts. The royal ancestral altars within the palace were adorned with brass bells, rattle staffs, ivory tusks and commemorative brass heads. At the center of the altar is a cast brass tableau depicting the Oba surrounded by his chiefs and courtiers.

The city, as well as its walls, was destroyed by the British during the punitive expedition of 1897. The British launched this expedition in retaliation for the killing of James Phillips, a British official, who had been killed along with his party by Benin warriors for venturing into the City during Igue, a sacred religious festival after being asked to stay away. Prior to this, there had been tensions between Oba Ovọnramwẹn Nọgbaisi, who exercised a monopoly on trade through Benin territory, and the Royal Niger Company, a mercantile company chartered by the British government, which was pushing for British interests in the then uncolonized Empire. This was escalated by Ovọnramwẹn’s refusal to sign the Gallwey Treaty, a free trade agreement with the British Protectorate. The tensions came to a head with the massacre of Phillips’ party. In February 1897, under Harry Rawson’s command, 1200 men comprising of British marines, sailors and Niger Coast Protectorate Forces captured and sacked Benin City, bringing an end to the Benin Empire. The British went on to loot ceremonial buildings and the Palace of Oba Ovọnramwẹn. A great portion of the city was burned down, including the Palace, and the Wall was partially destroyed. Oba Ovọnramwẹn was exiled to Calabar.

The looted artifacts found their way to England from where they were dispersed around the world through sale, actions, gifting, and loans. At least 3,000 Benin artworks are now in collections in major European and American museums including the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Royal Collection Trust, the Ethnological Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

These Bronzes have generated a lot of controversy over the years, and there has been a lot of debate on ownership and possible repatriation of thousands of these artifacts to Nigeria from institutions around the world. There have been promises from several institutions to begin pursuing the process of repatriation. In 2007, a consortium of Western museums joined Nigerians in a “Benin Dialogue Group” to open discussions about repatriation. In 2020, Germany announced plans to repatriate all of its Benin Bronzes. In March 2021, the University of Aberdeen in Scotland called its 1957 acquisition of a sculpture of an Oba head at auction in London “extremely immoral” and vowed to return it to its origins. The Humboldt Forum has also made pledges to return Benin Bronzes from its members’ collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution, the French state, and the city of Glasgow are among those who have made promises to return Benin Bronzes in their holdings. Earlier this year, after 123 years, the University of Aberdeen sculpture finally made its way back home to present-day Benin City. A Cockrel sculpture, Okukor, from Jesus College at the University of Cambridge was also returned to Benin City with the Oba sculpture. Germany has also handed over two Benin bronzes to Nigeria’s culture minister.

The Benin royal family in conjunction with the Nigerian government has plans to build a museum in present-day Benin City. The proposed museum, the Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA), is expected to host the most comprehensive collection of Benin Bronzes to date.

The bronze heads depicted in Nkem Okoro’s piece are used as representations of past Obas. At the start of his reign, each new Oba creates a shrine to the previous Oba, and a freestanding head was placed upon the shrine as a symbol of the character, qualities and essence of the previous Oba.

In the Edo tradition, the head signifies the character and destiny of an individual and is believed to be the receptacle of supernatural guidance; this belief is reflected in the level of detail present in these bronze heads. They show the regal cap worn by the Oba, which is made from coral beads woven in a lattice pattern. Strands of coral beads hang on either side of the Oba’s face, with larger bead clusters attached to them. Another large bead hangs from the center of the headdress to the forehead. The three raised marks above each eye are scarification marks called Ikharo. Intricate beads adorn the neck up to the mouth. A hole at the top of the head would usually hold an ivory tusk carved with significant events from the Oba’s reign. The tusk represented the bridge between the material world, agbon, and the spiritual world, erinmwim, where the ancestors reside.

Sources:

Frum, D. (2022). Who Benefits When Western Museums Return Looted Art? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/10/benin-bronzes-nigeria-return-stolen-art/671245/

Greenberger, A. (2022). London Museum to Return Ownership of 12 Benin Bronzes in Long-Awaited Repatriation. Art News. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/horniman-museum-benin-bronzes-repatriation-1234635961/

Greenberger, A. (2021). The Benin Bronzes, Explained: Why a Group of Plundered Artworks Continues to Generate Controversy. Art News. https://www.artnews.com/feature/benin-bronzes-explained-repatriation-british-museum-humboldt-forum-1234588588/

Koutonin, M. (2016). Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/18/story-of-cities-5-benin-city-edo-nigeria-mighty-medieval-capital-lost-without-trace

Marshall, A. (2020). This Art Was Looted 123 Years Ago. Will It Ever Be Returned? The Newyork Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/arts/design/benin-bronzes.html

Oltermann, P. (2021). Berlin’s plan to return Benin bronzes piles pressure on UK museums. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/mar/23/berlins-plan-to-return-benin-bronzes-piles-pressure-on-uk-museums

Olusoga, D. (2018). Yes, I’m a trustee of English Heritage. And I want the Benin bronzes returned. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/dec/15/yes-im-a-trustee-of-english-heritage-and-i-want-the-benin-bronzes-returned

Charles, .O. Osarumwense. (2014). Igue festival and the British invasion of Benin 1897: The violation of a peoples culture and sovereignty. African Journal of History and Culture, 6(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajhc2013.0170

Ross, E. G. (2022). Benin Chronology. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bnch/hd_bnch.htm